Renal Artery Stenosis Risk Calculator

This tool assesses your risk of acute kidney injury from ACE inhibitors based on clinical factors. According to research, 18.7% of people with bilateral renal artery stenosis develop kidney injury when taking these medications, compared to only 2.3% without stenosis.

When you take an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure or heart failure, you’re relying on a well-tested drug that’s helped millions. But if you have renal artery stenosis, that same medication can trigger a sudden, dangerous drop in kidney function - sometimes within days. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a well-documented, life-threatening contraindication that every doctor should check for before prescribing.

What happens when your kidney arteries narrow

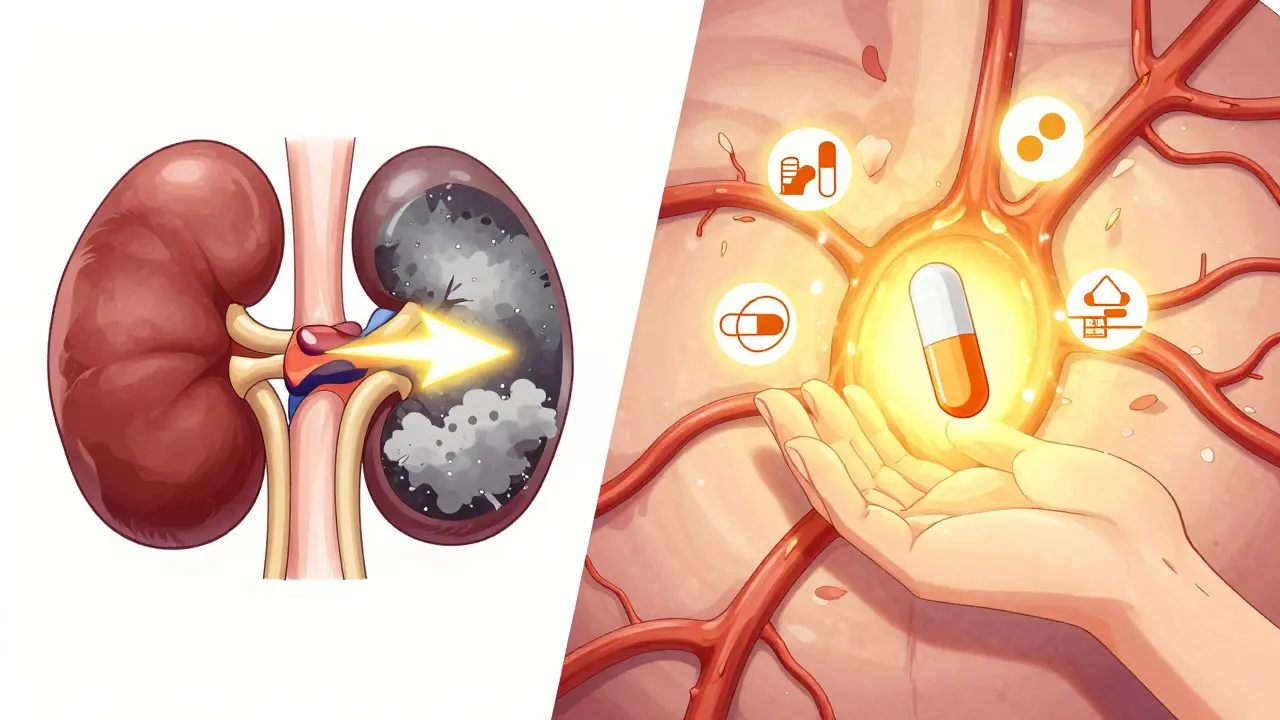

Your kidneys don’t just filter waste. They help control your blood pressure by releasing renin, a hormone that starts a chain reaction leading to angiotensin II. This chemical tightens blood vessels and, crucially, constricts the tiny artery leaving each kidney’s filtering unit (the efferent arteriole). Why does that matter? In a kidney with a narrowed artery, blood flow is already low. The body compensates by squeezing that efferent arteriole harder. That keeps pressure high inside the glomerulus - the filtering part - so the kidney can still work.

Think of it like a garden hose with a kink. If you pinch the middle, water flow drops. But if you squeeze the end tightly, pressure builds up behind the pinch, and water still sprays out. That’s what angiotensin II does: it squeezes the end to keep the filter running, even when the supply line is blocked.

How ACE inhibitors break this balance

ACE inhibitors stop your body from making angiotensin II. That’s great for lowering blood pressure - but in a kidney with stenosis, it’s disastrous. Without that angiotensin II squeeze, the efferent arteriole opens up. Pressure in the glomerulus plummets. And when that happens, filtration stops. Your kidneys can’t clean your blood anymore.

Studies using micropuncture in animals and humans show this drop is real and sharp. In stenotic kidneys, glomerular pressure can fall by 25-30% within hours of taking an ACE inhibitor. In one classic study from 1988, pressure dropped from 48.5 mm Hg to 35.7 mm Hg after just one dose of captopril. That’s not a minor fluctuation. That’s enough to shut down kidney function.

The numbers don’t lie: how often does this happen?

A 2018 study of 1,247 people starting ACE inhibitors found that 18.7% of those with bilateral renal artery stenosis developed acute kidney injury - defined as a rise in creatinine of more than 30%. That’s nearly 1 in 5. In contrast, only 2.3% of people without stenosis had the same reaction. The risk is highest in people with stenosis in both kidneys, or in those with only one working kidney. In those cases, the kidney has no backup. No safety net.

The damage usually shows up 7-10 days after starting the drug. That’s why guidelines recommend checking kidney function - serum creatinine and potassium - before you start, and again 10 days after. If creatinine jumps more than 30%, stop the ACE inhibitor immediately. Most of the time, kidney function returns to normal within a week or two after stopping the drug. But if the low blood flow lasts more than 72 hours, permanent damage can occur.

It’s not just ACE inhibitors - ARBs are just as risky

Some patients are told to switch to an ARB (like losartan or valsartan) if they can’t take ACE inhibitors. That’s a dangerous misunderstanding. ARBs block the same final pathway - angiotensin II receptors. So if angiotensin II is needed to keep your kidney filtering, blocking its action - whether by stopping its production or its effect - does the same damage.

Guidelines from KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) and the American Heart Association both list bilateral renal artery stenosis or stenosis in a solitary kidney as a contraindication for both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. There’s no safe substitute here.

Who’s at risk - and how to spot it

You don’t need to be a specialist to recognize who’s at risk. Look for these red flags:

- High blood pressure that started suddenly, especially after age 50

- Unexplained kidney function decline (rising creatinine)

- A whooshing sound (bruit) heard over the abdomen during a physical exam

- Worsening kidney function after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB

These aren’t rare. One study found that 6.8% of patients with high blood pressure and kidney problems had significant renal artery stenosis. That’s nearly 1 in 15. Yet a 2020 study found that over 22% of patients with known bilateral stenosis were still being prescribed ACE inhibitors - a clear sign that many clinicians miss the diagnosis.

What to do if you’re at risk

If you have any of the red flags above, ask for a renal artery duplex ultrasound. It’s non-invasive, widely available, and has 86% sensitivity and 92% specificity for detecting significant stenosis. If the test shows narrowing in both arteries - or in your only functioning kidney - ACE inhibitors and ARBs are off the table.

Alternative blood pressure options exist. Calcium channel blockers (like amlodipine) and diuretics (like chlorthalidone) are often safer choices. Beta-blockers may also be used, depending on your heart health. The goal isn’t to avoid treating high blood pressure - it’s to treat it safely.

The bottom line

ACE inhibitors are powerful tools. But they’re not safe for everyone. In renal artery stenosis, they don’t just cause side effects - they can cause sudden kidney failure. The science is clear. The guidelines are consistent. The risk is real. If you’re taking one and have unexplained kidney changes, don’t wait. Talk to your doctor. Get tested. Your kidneys are counting on it.

Mayank Dobhal

February 8, 2026 AT 04:47Savannah Edwards

February 8, 2026 AT 09:46AMIT JINDAL

February 9, 2026 AT 23:27Gouris Patnaik

February 10, 2026 AT 02:40Ashley Hutchins

February 10, 2026 AT 12:54Mary Carroll Allen

February 10, 2026 AT 22:16Ariel Edmisten

February 11, 2026 AT 01:44Heather Burrows

February 12, 2026 AT 13:23Lakisha Sarbah

February 13, 2026 AT 13:26