Contact Dermatitis Immune Response Simulator

Select an allergen that commonly causes allergic contact dermatitis:

These substances act as haptens and bind to skin proteins.

Click below to simulate first-time exposure to the selected allergen:

This initiates the sensitization phase of the immune response.

After sensitization, click below to simulate re-exposure:

This triggers the delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction.

View how immune cells respond during each stage:

Click "Simulate First Exposure" to begin the simulation.

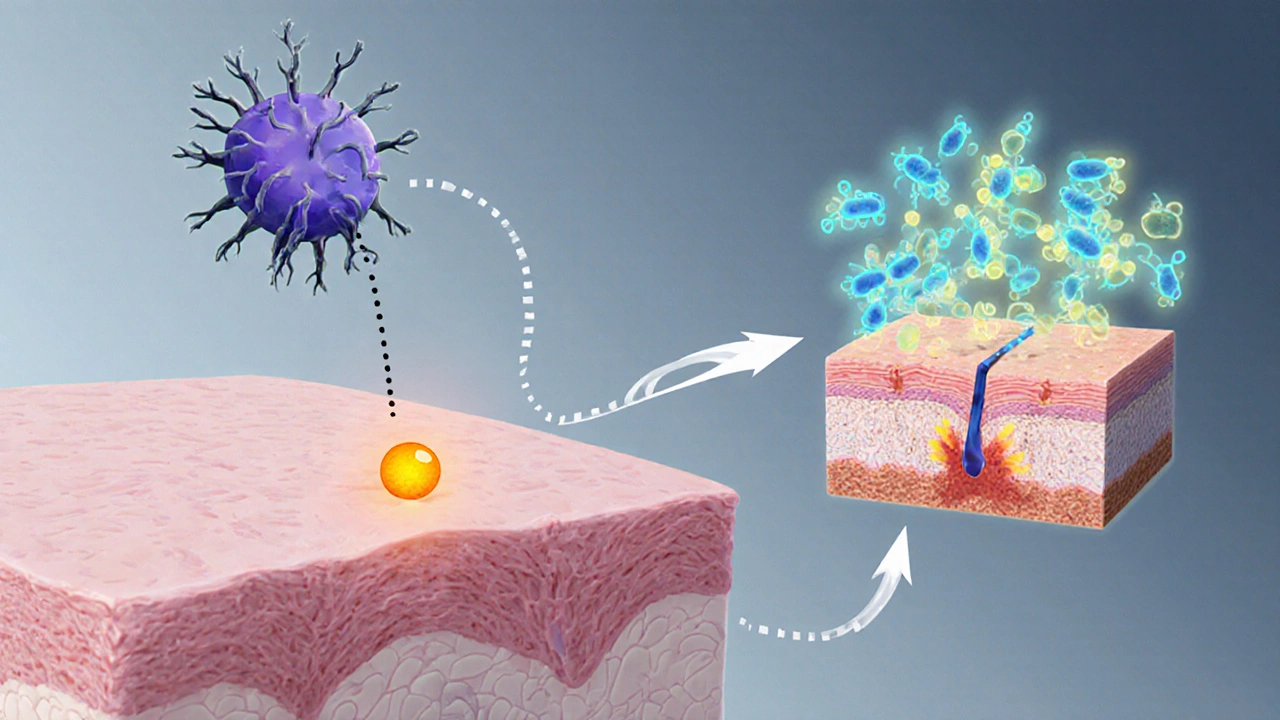

Langerhans Cells

Specialized dendritic cells in the epidermis that capture allergens and present them to T-cells.

T-Cells

Sensitized T-cells release cytokines upon re-exposure, triggering inflammation.

Cytokines

Signaling proteins like interferon-γ and interleukin-2 that drive immune cell recruitment.

The type IV hypersensitivity reaction is responsible for the delayed onset (24-48 hours) of allergic contact dermatitis symptoms.

Key Takeaways

- Contact dermatitis is a skin reaction triggered by irritants or allergens.

- The immune system drives allergic reactions via a typeIV hypersensitivity pathway.

- Langerhans cells, T‑cells and cytokines are the main players in the inflammatory cascade.

- Preventing flare‑ups involves protecting the skin barrier and avoiding known triggers.

- Seek medical care if symptoms spread, blister, or don’t improve with over‑the‑counter treatment.

Picture this: you wash your hands after gardening and notice a red, itchy patch on your forearm an hour later. That’s a classic sign of contact dermatitis. While the rash looks simple, the biology underneath is anything but. By the end of this read you’ll know exactly why your skin reacts, which immune cells are pulling the strings, and how to keep those annoying flare‑ups at bay.

What Is Contact Dermatitis?

Contact Dermatitis is a skin reaction that develops after direct exposure to certain substances, leading to redness, itching, swelling, and sometimes blisters. It falls into two main categories: irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Both look similar on the surface, but the mechanisms that cause them are quite distinct.

The Immune System’s Role in Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Immune System a network of cells, tissues, and organs that defends the body against harmful agents is the hidden engine behind allergic contact dermatitis. Unlike a simple chemical burn, ACD is an immune‑mediated response known as a typeIV hypersensitivity reaction.

The process begins when a small molecule, called a hapten, binds to skin proteins. This complex is then captured by Langerhans cells specialized dendritic cells residing in the epidermis that act as antigen‑presenting cells. After uptake, Langerhans cells migrate to nearby lymph nodes, where they present the hapten‑protein complex to naïve T cells a type of lymphocyte that orchestrates adaptive immune responses.

Upon re‑exposure to the same allergen, these sensitized T cells release a cocktail of Cytokines signaling proteins that direct inflammation and immune cell recruitment such as interferon‑γ and interleukin‑2. The cytokine surge attracts more immune cells to the skin, leading to the characteristic redness, edema, and itching.

Histamine, while famously linked to immediate allergic reactions, plays a smaller role in ACD. Instead, the delayed response is driven by cytokine‑mediated recruitment of macrophages and additional T cells, which explains why symptoms often appear 24‑48hours after contact.

Irritant vs. Allergic Contact Dermatitis: How Do They Differ?

| Aspect | Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD) | Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD) |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger Type | Chemical or physical irritants (e.g., detergents, solvents) | Allergens that act as haptens (e.g., nickel, poison ivy) |

| Immune Involvement | Minimal; direct damage to skin cells | Requires sensitization; T‑cell mediated |

| Onset | Minutes to hours after exposure | 24‑48hours after re‑exposure |

| Typical Symptoms | Burning, stinging, immediate redness | Painful itching, spreading erythema, sometimes vesicles |

| Risk of Chronicity | Low if irritant removed promptly | Higher; repeated exposure can lead to chronic dermatitis |

Understanding these differences helps you choose the right treatment. For ICD, washing the area with cool water and applying barrier creams is often enough. For ACD, you’ll need anti‑inflammatory topical steroids and strict avoidance of the allergen.

Common Triggers and Their Interaction with the Skin Barrier

The skin’s outermost layer, the Skin Barrier a protective matrix of lipids and proteins that prevents water loss and blocks external irritants, plays a crucial role in both forms of dermatitis. When the barrier is compromised-by chronic washing, low humidity, or genetic factors-substances penetrate more easily, increasing the chance of an immune reaction.

Typical irritants include:

- Strong soaps and detergents

- Alcohol‑based hand sanitizers

- Acidic or alkaline cleaning agents

Common allergens are:

- Nickel (found in jewelry, metal fasteners)

- Fragrance mixes in cosmetics

- Poison ivy, oak, and sumac (urushiol oil)

- Latex proteins

Research from 2023 shows that individuals with a compromised skin barrier are up to 3.5times more likely to develop ACD after first exposure to a sensitizer.

Prevention and Management Strategies

Prevention starts with protecting the barrier. Choose fragrance‑free moisturizers that contain ceramides, glycerin, or hyaluronic acid. Apply them after washing while the skin is still slightly damp to lock in moisture.

When you know you’ll be handling a potential irritant, wear protective gloves made of nitrile rather than latex, because latex itself can be an allergen. If gloves are not an option, apply a barrier cream containing dimethicone before exposure.

If a rash does appear, the first‑line treatment for mild ICD is a cool compress and a non‑prescription emollient. For ACD, over‑the‑counter hydrocortisone 1% can reduce inflammation, but stronger prescription steroids may be required for extensive or persistent cases.

Adjunct therapies such as oral antihistamines can help control itching, even though histamine isn’t the primary driver in ACD. In chronic cases, a dermatologist might recommend calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus) to modulate the T‑cell response without the skin‑thinning side effects of steroids.

When to Seek Professional Care

If your rash spreads beyond the initial contact area, forms blisters, or is accompanied by fever, it’s time to see a doctor. Patch testing-a controlled application of common allergens-can pinpoint the exact trigger, allowing you to avoid future flare‑ups.

Persistent symptoms lasting more than two weeks despite proper self‑care may indicate an underlying condition such as atopic dermatitis or a secondary infection, both of which require tailored treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can contact dermatitis become chronic?

Yes. Repeated exposure to the same irritant or allergen can damage the skin barrier and keep the immune system in a heightened state, leading to chronic inflammation and thickened skin (lichenification).

Is a skin patch test painful?

The test involves applying small amounts of allergens to adhesive patches on the back. Most people feel only mild itching or a slight tingling sensation; it’s generally well tolerated.

Do over‑the‑counter steroid creams work for allergic dermatitis?

For mild to moderate ACD, a 1% hydrocortisone cream can reduce redness and itching. Severe cases often need a stronger prescription steroid, such as clobetasol, applied under medical supervision.

Can I prevent contact dermatitis by using moisturizers?

Regularly applying moisturizers that restore lipids helps keep the skin barrier intact, which lowers the risk of both irritant and allergic reactions. Look for products with ceramides, niacinamide, or petrolatum.

Are there natural remedies that work for contact dermatitis?

Aloe vera gel and colloidal oatmeal can soothe itching and provide a mild anti‑inflammatory effect. However, they should complement-not replace-medical treatments for moderate to severe flare‑ups.

Deborah Summerfelt

October 5, 2025 AT 14:04Imagine your skin as a tiny battlefield where chemicals try to sneak past the guard posts and the immune system decides whether to call in the troops or just shrug it off. The whole drama starts when a hapten latches onto a protein and makes the Langerhans cells send a memo to the lymph nodes. Once that memo arrives, naïve T‑cells get the memo and become the over‑eager soldiers that later cause the itching you can’t ignore. If you think it’s just a rash, you’re missing the whole cascade of cytokines that turn a simple bump into a full‑blown protest. That’s why a good moisturizer isn’t just a feel‑good thing; it’s actually reinforcing the barrier that keeps the invaders from getting a foothold.

Maud Pauwels

October 5, 2025 AT 15:27the article kinda nails the basics but could use more on barrier repair its worth a quick read

Scott Richardson

October 5, 2025 AT 16:51Listen folks America knows the best skin care products so if you’re complaining about dermatitis just grab a proper moisturizer and stop whining

Laurie Princiotto

October 5, 2025 AT 18:14oh great another “great” post 🙄

Justin Atkins

October 5, 2025 AT 22:24While the exposition admirably delineates the immunologic cascade, it would benefit from a deeper exploration of the molecular interactions between hapten‑protein conjugates and pattern‑recognition receptors on Langerhans cells. Moreover, the temporal dynamics of cytokine secretion-particularly interferon‑γ versus interleukin‑2-deserve quantitative clarification, as they underlie the severity of the delayed hypersensitivity. A brief discussion of therapeutic modulation, perhaps via calcineurin inhibitors, would further enrich the narrative. Nonetheless, the clarity of the visual simulator provides an accessible conduit for lay learners to grasp these otherwise esoteric processes.

June Wx

October 5, 2025 AT 23:47Yo the simulation is lit! It actually shows how those tiny cells go crazy when you get re‑exposed. I feel like I totally get why my nickel bracelet always makes my wrist itch now.

kristina b

October 6, 2025 AT 03:57In contemplating the manifold intricacies of contact dermatitis, one is inevitably drawn to the profound symbiosis between external haptens and the endogenous immunologic architecture. The initial encounter, wherein a diminutive molecule clandestinely adheres to dermal proteins, sets in motion a cascade of events that eloquently illustrates the elegance of immunological vigilance. Langerhans cells, those vigilant sentinels of the epidermis, internalize the hapten‑protein complex with a deliberateness that belies their microscopic stature. Their migration to regional lymph nodes is not a mere transit but a purposeful pilgrimage wherein antigenic fragments are presented to naïve T‑cells in a context that demands specificity. Upon recognition, these T‑cells undergo clonal expansion, a process that, though rapid, is meticulously orchestrated by a milieu of cytokines and co‑stimulatory signals. The subsequent re‑exposure to the identical hapten precipitates a recall response, wherein sensitized T‑cells discharge an arsenal of interferon‑γ, interleukin‑2, and other mediators, thereby recruiting macrophages and additional lymphocytes to the site of insult. This coordinated influx manifests clinically as the erythema, edema, and pruritus that characterize the delayed‑type hypersensitivity reaction. It is noteworthy that, unlike the immediacy of histamine‑driven urticaria, the temporal lag of twenty‑four to forty‑eight hours underscores the adaptive nature of this response. Moreover, the integrity of the stratum corneum serves as a pivotal determinant of hapten penetration; a compromised barrier, whether by chronic irritation or genetic predisposition, markedly lowers the threshold for sensitization. Preventive strategies, therefore, must prioritize barrier reinforcement through emollients enriched with ceramides, glycerin, or hyaluronic acid, applied to moist skin to maximize restoration. In parallel, avoidance of known allergens-nickel, fragrance mixes, urushiol, latex-remains the cornerstone of prophylaxis. Therapeutically, topical corticosteroids attenuate the inflammatory cascade, yet their prolonged use necessitates vigilance for cutaneous atrophy, prompting consideration of steroid‑sparing agents such as tacrolimus. Ultimately, the confluence of cellular immunology, barrier physiology, and patient‑centered management delineates a comprehensive paradigm for confronting contact dermatitis. The pedagogical value of interactive simulators, as presented herein, lies in their capacity to render abstract immunologic concepts palpable, thereby fostering both clinical acumen and patient empowerment.

Ida Sakina

October 6, 2025 AT 05:21The moral imperative is clear protect the skin barrier lest we invite needless suffering

Amreesh Tyagi

October 6, 2025 AT 09:31i think the whole type iv thing is overblown

Brianna Valido

October 6, 2025 AT 10:54Love how this breaks down the science 🌟 keeping your skin happy is totally doable 😊

Caitlin Downing

October 6, 2025 AT 15:04Honestly this post does a great job but i wish it talked more about how stress can make the rash worse lol the info is solid and easy 2 follow

Robert Jaskowiak

October 6, 2025 AT 16:27Oh wow, because we all needed a step‑by‑step guide to get itchy, thanks for the tutorial 🙃

Julia Gonchar

October 6, 2025 AT 20:37Just a heads up the best way to test for nickel allergy is a patch test, not just guessing from a rash

Annie Crumbaugh

October 6, 2025 AT 22:01Cool info, thanks.