Phenytoin-Warfarin INR Tracker

Current Status

Next Monitoring

Potential Risk

Critical Actions

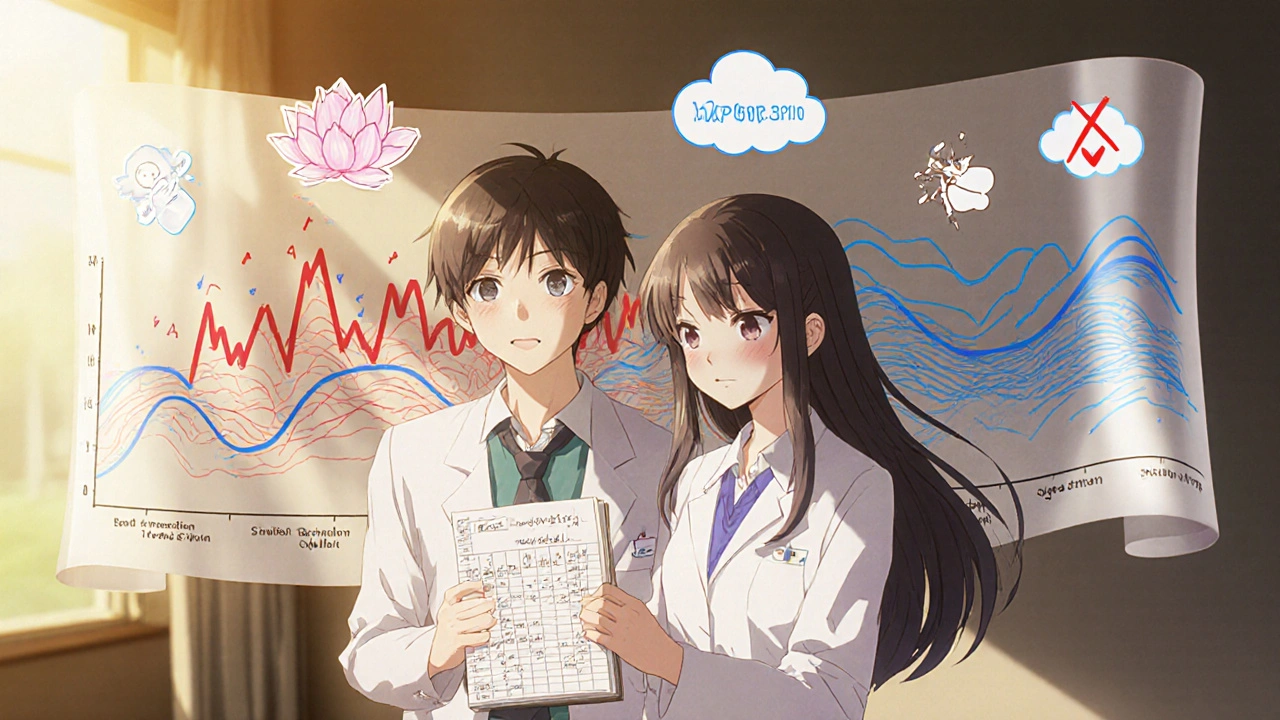

INR likely to increase due to protein displacement

INR may stabilize as displacement effect fades

INR likely to decrease due to enzyme induction

INR increases over 10-14 days as enzyme activity decreases

When you take phenytoin and warfarin together, your body doesn’t just handle two drugs-it handles a chemical tug-of-war that can send your INR soaring one week and crashing the next. This isn’t a theoretical concern. It’s a real, life-threatening interaction that shows up in emergency rooms, clinics, and nursing homes across the country. And if you’re on both medications, you need to know exactly what’s happening inside you-not just what your doctor says.

What’s Actually Going On Between Phenytoin and Warfarin?

Phenytoin doesn’t just interfere with warfarin-it flips it upside down, twice. The first hit comes fast. Within 24 to 72 hours of starting phenytoin, your INR can jump. That’s because phenytoin is sticky. It binds to albumin in your blood with such force that it kicks warfarin off its protein anchors. Warfarin is 99% bound to proteins under normal conditions. When phenytoin pushes it loose, suddenly more warfarin is floating around unbound-and active. That’s the free fraction. That’s what actually thins your blood. So even if your total warfarin dose hasn’t changed, your body is now exposed to more of it. This is why INR spikes early. But here’s the twist: that spike doesn’t last. By day 3 to 5, your body adjusts. The free warfarin levels settle back down. But then, something deeper kicks in. Phenytoin starts turning on your liver’s drug-processing machines. Specifically, it cranks up CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 enzymes-those are the same enzymes that break down warfarin. Over the next 7 to 14 days, your liver gets so good at destroying warfarin that you might need two to five times your original dose just to stay in range. That’s not a typo. Some patients go from 5 mg a day to 20 mg or more. And if you don’t catch this shift, your INR will drop below 2.0. That’s not just risky-it’s dangerous. You’re no longer protected from clots.Why Some People Get Hit Harder Than Others

Not everyone reacts the same way. Genetics play a huge role. If you carry the CYP2C9*2 or CYP2C9*3 variant, your liver is already slow at breaking down warfarin. When phenytoin comes along and forces your liver to speed up, the contrast is brutal. Your body has to work much harder to compensate. That means bigger dose increases-and more room for error. People with these variants often need to be monitored more closely, sometimes even before phenytoin is even started. Low albumin levels make things worse too. If you’re malnourished, have liver disease, or are elderly, your protein levels might be below 3.5 g/dL. That means there’s less albumin to go around. When phenytoin competes for binding sites, it displaces warfarin more easily. Even small changes in binding can cause big swings in INR. One study showed that patients with low albumin had free warfarin levels jump by 30% within 48 hours of phenytoin initiation. That’s enough to cause bleeding in someone already on the edge. And then there’s phenytoin’s own quirks. It doesn’t follow normal dose-response rules. A 5 mg increase might do nothing. The next 5 mg might send your levels from 12 to 25 mcg/mL. That’s nonlinear pharmacokinetics. It’s unpredictable. Combine that with warfarin’s own sensitivity, and you’ve got a perfect storm.What Happens When You Stop Phenytoin?

Stopping phenytoin is just as risky as starting it. You might think, “If it made my INR drop, then taking it away should make it go up.” But it doesn’t happen overnight. The enzyme induction doesn’t vanish when you quit the drug. It fades slowly. Over 10 to 14 days, your liver gradually slows down warfarin metabolism. Your INR creeps up. If you don’t reduce your warfarin dose during this time, you’re heading straight for bleeding. Clinicians often miss this. They focus on the start-up phase and forget the wind-down. A patient who’s been stable on 20 mg of warfarin for months might suddenly start bruising easily or notice blood in their urine after phenytoin is stopped. That’s not random. That’s delayed enzyme withdrawal. The fix? Drop the warfarin dose by 25% to 50% within a few days of stopping phenytoin-and monitor INR every 2 to 3 days until it stabilizes.

How to Monitor and Manage This Right

The only reliable way to manage this interaction is with frequent, consistent INR checks. No guesswork. No “I’ll adjust next week.”- When phenytoin is started: Check INR every 2 to 3 days for the first two weeks. Then weekly until stable.

- When phenytoin is stopped: Check INR every 2 to 3 days for at least two weeks after discontinuation.

- Never adjust warfarin based on a single INR. Look at the trend. A single high reading might be the displacement effect-temporary. A rising INR over 7 days? That’s enzyme withdrawal.

- Don’t assume your dose is “set.” Even after stabilization, recheck INR monthly. Changes in diet, illness, or other meds can still throw things off.

Are There Better Alternatives?

Yes-and you should ask about them. If you’re on warfarin and need an antiepileptic, phenytoin is not your best choice. It’s outdated for this reason. Levetiracetam, gabapentin, and pregabalin don’t induce liver enzymes. They don’t displace proteins. They don’t mess with INR. They’re safer. In fact, major guidelines now recommend these as first-line for patients on anticoagulants. And what about switching from warfarin? Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like apixaban and rivaroxaban are great-until you add phenytoin. Those drugs get broken down by the same enzymes. Phenytoin can slash their levels by 70% or more. That’s why DOACs are often contraindicated with enzyme inducers. So if you’re on phenytoin, warfarin might still be your only viable oral option. That makes managing the interaction even more critical.

What to Do If You’re Already on Both

If you’re already taking phenytoin and warfarin:- Keep a log of your INR values and dates. Bring it to every appointment.

- Know your baseline. What was your INR before phenytoin? What’s your usual warfarin dose?

- Watch for signs of bleeding: unusual bruising, nosebleeds, dark stools, headaches, dizziness.

- Don’t start or stop any other meds-supplements, OTC painkillers, even herbal teas-without checking with your pharmacist.

- Ask if you’re a candidate for CYP2C9 or VKORC1 genetic testing. It won’t change everything, but it might explain why your doses are so unpredictable.

Why This Still Matters in 2025

You might think, “With all the new drugs, why is anyone still using phenytoin?” Because it’s cheap. Because it’s effective in status epilepticus. Because in rural areas or developing countries, it’s still the only option. And because millions of people are still on warfarin-about 2.6 million in the U.S. alone. Even with DOACs, warfarin hasn’t disappeared. It’s still the go-to for mechanical heart valves, antiphospholipid syndrome, and certain clotting disorders. This interaction isn’t going away. It’s just becoming more concentrated in high-risk patients. That means the people who need to understand it the most-patients, nurses, pharmacists-are the ones least likely to have access to specialists. That’s why clear, practical guidance matters more than ever.Can phenytoin cause bleeding even if my INR is normal?

Yes, but only during the initial phase. When phenytoin first displaces warfarin from proteins, your total warfarin level might look normal on a lab test, but your free (active) warfarin level spikes. Standard INR tests measure clotting time, which reflects active warfarin. So if your INR is normal during this phase, you’re likely not in danger. But if your INR suddenly jumps without a dose change, that’s the displacement effect. Always report any new bruising or bleeding-even if your INR seems fine.

How long does it take for phenytoin to fully affect warfarin?

It happens in two stages. The protein displacement effect kicks in within 24 to 72 hours. The enzyme induction effect takes longer-usually 7 to 10 days to become significant, and up to 14 days to reach full strength. That’s why monitoring needs to last at least two weeks after starting phenytoin. Don’t assume you’re safe after a week.

Should I avoid phenytoin completely if I’m on warfarin?

Not necessarily, but you should question why it’s being used. If you’re being prescribed phenytoin for a seizure disorder, ask if alternatives like levetiracetam or gabapentin are possible. These don’t interfere with warfarin. Phenytoin should only be used if no other options work-especially if you’re at risk for bleeding or have unstable INR. It’s not the first-line choice anymore.

Can I take ibuprofen or aspirin with phenytoin and warfarin?

Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen. They increase bleeding risk on their own and can also affect kidney function, which changes how warfarin is cleared. Aspirin is sometimes used with warfarin under strict supervision, but combining it with phenytoin adds another layer of risk. Always check with your pharmacist before taking any OTC pain reliever. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is generally safer, but even that can affect INR at high doses over time.

Is genetic testing worth it for this interaction?

It can be. If you’ve had unpredictable INR swings in the past, or if you’re a poor metabolizer of warfarin (CYP2C9*2 or *3 variants), genetic testing can help explain why your doses are so hard to manage. It won’t eliminate the need for monitoring, but it can give your provider a better starting point. Many hospitals now offer this testing as part of anticoagulation clinics. Ask if it’s available to you.

What if I miss a dose of phenytoin?

Missing a dose of phenytoin can be dangerous. Because it has nonlinear pharmacokinetics, even small drops in blood levels can cause seizures. But it can also affect warfarin. If phenytoin levels drop, enzyme induction slows, which can cause your INR to rise over the next few days. If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember-if it’s within a few hours. If it’s been longer, skip it and go back to your schedule. Don’t double up. And monitor your INR more closely for the next week.

Ragini Sharma

November 22, 2025 AT 16:08so phenytoin just kicks warfarin off its protein couch like a rude roommate? lol. i swear if my INR jumps again i’m gonna start carrying a blood thinner calculator in my purse. also why is everyone still using phenytoin? it’s like prescribing a typewriter in 2025.

Linda Rosie

November 23, 2025 AT 13:01Clear, evidence-based guidance. Essential reading for clinicians managing anticoagulation in patients with seizure disorders.

Vivian C Martinez

November 24, 2025 AT 04:52This is exactly the kind of practical, no-nonsense info that saves lives. If you’re on both meds, print this out and tape it to your fridge. You’re not being paranoid-you’re being smart.

Ross Ruprecht

November 24, 2025 AT 23:16meh. i just take my pills and hope for the best. why does this even matter? my doc knows what they’re doing.

Lisa Lee

November 25, 2025 AT 22:56Of course Americans are still using this outdated junk. We don’t even have real healthcare. In Canada, we’d be on levetiracetam by day one. This is why your hospitals are drowning.

JD Mette

November 27, 2025 AT 06:45I’ve seen patients bleed out because this interaction was missed. It’s not theoretical. It’s not rare. It’s systemic. Please, if you’re reading this and you’re on both-talk to your pharmacist. Don’t wait for the emergency room.

Charmaine Barcelon

November 28, 2025 AT 11:32STOP! STOP! STOP! You’re all ignoring the real issue: you’re not tracking your INR daily! You think a monthly check is enough?!?!? NO! NO! NO! You need to test every day! Every. Single. Day! Or you’re going to die!

Karla Morales

November 30, 2025 AT 06:12📊 INR trends: 2.1 → 4.8 → 1.6 → 3.0 📉

📉 Enzyme induction: CYP2C9↑ 300%

💉 Free warfarin: +30% within 48h

🧬 CYP2C9*3 carriers: 15% of population

⚠️ DOACs: contraindicated with phenytoin

✅ Levetiracetam: 0 enzyme interaction

🩸 Bleeding risk: 7x higher without monitoring

💡 Home INR device: recommended by ACCP 2024

📉 Dose adjustment window: 7–14 days post-initiation

📌 Log your INR. Every. Single. Time.

Javier Rain

December 1, 2025 AT 03:15Listen up. This isn’t just medical trivia-it’s your life. If you’re on phenytoin and warfarin, you’re playing Russian roulette with your blood. But here’s the good news: you can win. Track your INR. Ask for home testing. Demand genetic screening. Don’t let your doctor rush you. You’re not a number-you’re a person who deserves to stay alive.

Laurie Sala

December 1, 2025 AT 06:20I’ve been on both for 3 years… I’ve had 3 ER trips… I’ve cried in the bathroom after my INR spiked… I don’t sleep anymore… I check my INR at 3 a.m. because I’m terrified… WHY DOESN’T ANYONE TALK ABOUT THIS? I feel so alone…

Lisa Detanna

December 1, 2025 AT 21:31In my community, many elders are on warfarin and prescribed phenytoin because it’s cheap. No one explains the risks. This post? It’s a gift. I’m printing it for my mom’s clinic. Thank you for writing this.

Demi-Louise Brown

December 3, 2025 AT 03:11Consistent monitoring is the only reliable safeguard. Document trends, not single values. Advocate for home INR devices. Ask about alternatives. Knowledge is power-and in this case, it’s life.

Matthew Mahar

December 3, 2025 AT 08:34wait… so if i miss a dose of phenytoin my warfarin might go crazy? like… i just took a nap and now i’m gonna bleed out? this is insane. i’m gonna start carrying a blood test kit in my backpack. also i think i spelled phenytoin wrong in my notes… oops