When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a complex science designed to prove it works the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence testing comes in. It’s not just about matching ingredients-it’s about proving the drug gets into your bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the original. And there are two main ways to do it: in vivo and in vitro. Knowing when each is used helps explain why some generics are approved quickly, while others take years and cost millions.

What Is In Vivo Bioequivalence Testing?

In vivo bioequivalence testing means testing the drug inside a living human. It’s the gold standard for most generic drugs. Here’s how it works: 24 healthy volunteers take both the brand-name drug and the generic version, usually in a crossover design-meaning half take the generic first, then the brand after a washout period, and the other half do the reverse. Blood samples are drawn over 24 to 72 hours to measure how much of the drug enters the bloodstream and how fast. The key numbers regulators look at are Cmax (the highest concentration in blood) and AUC (the total exposure over time). For the drugs to be considered bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values between the generic and brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s not a guess-it’s a strict, statistically validated range set by the FDA and EMA. If the generic stays within those bounds, it’s approved. This method works best for oral tablets and capsules, especially immediate-release forms. It’s sensitive. It catches differences in how the drug dissolves, how it’s absorbed, or even how food affects it. But it’s expensive. A single study can cost between $500,000 and $1 million. It takes 3 to 6 months to complete, including screening, dosing, and follow-up. And yes, it requires human volunteers, which raises ethical and logistical hurdles.What Is In Vitro Bioequivalence Testing?

In vitro means “in glass”-so this testing happens in a lab, outside the body. Instead of drawing blood from people, scientists measure physical and chemical properties of the drug. The most common method is dissolution testing: placing the tablet in a beaker of fluid that mimics stomach or intestinal conditions, then measuring how quickly the drug releases. But it’s not just about dissolving. For inhalers, they test droplet size using laser diffraction. For nasal sprays, they use cascade impactors to measure how particles deposit in the nose. For topical creams, they check how much drug comes out of the base over time. These tests are precise. A good dissolution method might have a coefficient of variation under 5%, compared to 10-20% in human studies. That means less noise, more reliability. The big advantage? Speed and cost. In vitro testing can be done in 2 to 4 weeks for under $150,000. No human subjects. No ethics board delays. No travel to clinical sites. That’s why companies love it-for the right products.When Do Regulators Accept In Vitro Testing Alone?

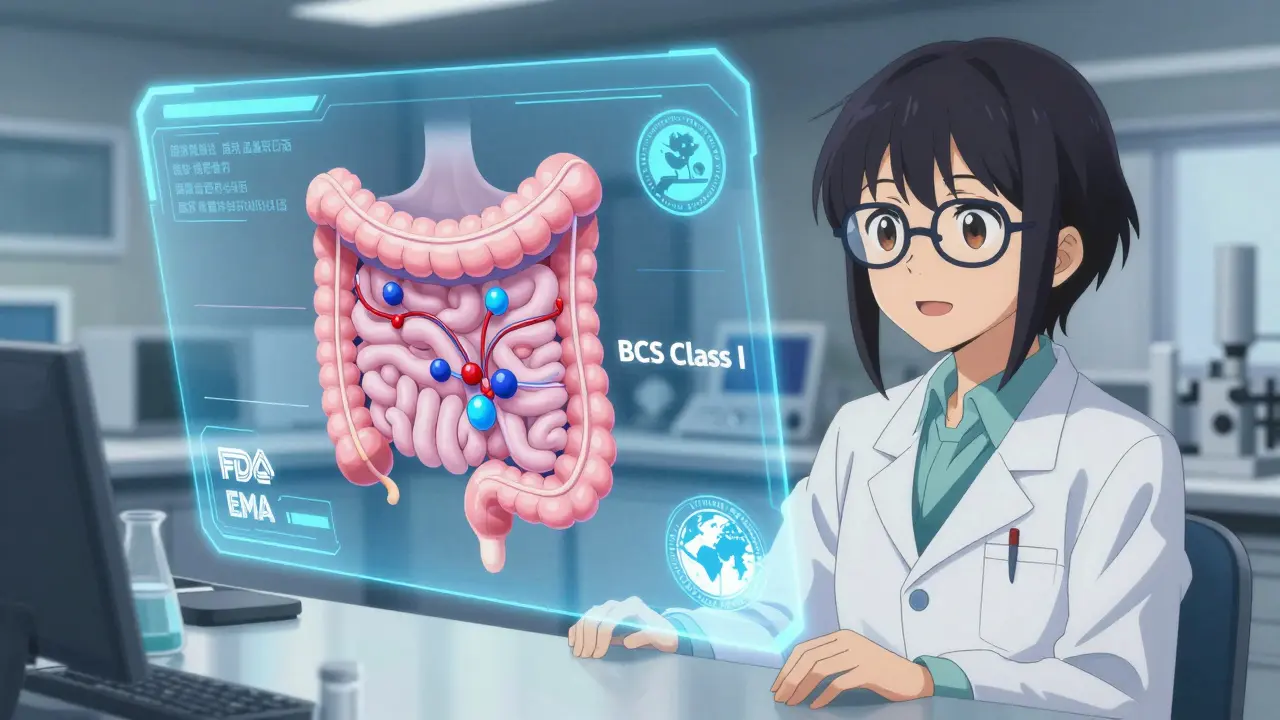

You can’t just swap out a human study for a lab test. The FDA and EMA have clear rules. In vitro testing is accepted as a full replacement for in vivo testing only under specific conditions. First, for BCS Class I drugs-those that are highly soluble and highly permeable. These drugs absorb easily and predictably. In 2021, the FDA granted biowaivers (approval without human testing) for 78% of generic applications for BCS Class I drugs. That’s because dissolution profiles under multiple pH conditions (1.2, 4.5, 6.8) reliably predict how the drug behaves in the gut. Second, for complex delivery systems where in vivo testing doesn’t make sense. Take metered-dose inhalers. You can’t ethically or practically test 24 people breathing in different aerosol patterns to see if they deliver the same dose. Instead, regulators accept cascade impactor data showing particle size and dose consistency. In 2022, the FDA approved the first generic budesonide nasal spray based solely on in vitro data. That was a milestone. Third, when there’s a validated in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC). This means lab results perfectly predict what happens in the body. For example, a modified-release theophylline product showed an r² value above 0.95 between dissolution rate and plasma concentration. That’s strong enough for regulators to trust the lab data.

When Is In Vivo Testing Still Required?

Despite advances, human testing is still mandatory in many cases. If the drug has a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or cyclosporine-small differences in absorption can be dangerous. For these, regulators tighten the bioequivalence window to 90-111%. In vitro methods can’t reliably detect those subtle differences yet. If the drug’s absorption depends on food, you need a fed-state study. In vitro tests use artificial fluids that can’t replicate the real-time changes in stomach acidity, bile flow, or gut motility after eating. A 2018 study showed in vitro methods predicted bioequivalence correctly for 92% of BCS Class I drugs, but only 65% of BCS Class III drugs-those with low solubility. That’s a big gap. For topical products that act locally (like antifungal creams), in vivo testing isn’t always needed. But if there are reports of inconsistent results in patients-like one user’s rash clearing up and another’s not-regulators may demand an in vivo study later. One company learned this the hard way: their topical antifungal, approved via in vitro data, required a $850,000 follow-up study after adverse event reports.Why the Industry Is Pushing for More In Vitro Testing

Cost and speed aren’t the only reasons. In vitro testing reduces variability. Human biology is messy. One person’s gut pH, enzyme levels, or transit time can change results. Lab conditions? You control them perfectly. A senior scientist at Teva reported saving $1.2 million and 8 months by switching from in vivo to in vitro testing for a BCS Class I product. The catch? It took 3 months to develop the dissolution method to FDA standards. That’s the trade-off: upfront effort for long-term savings. Regulators are responding. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on nasal sprays and inhalers says in vitro testing alone can be sufficient. The European Medicines Agency approved 214 biowaivers in 2022-up 27% from 2020. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) now aligns U.S., EU, and Japanese standards on this. But the real shift is in modeling. The FDA is now accepting physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models-computer simulations that predict how a drug behaves in different people. These models, combined with in vitro data, are becoming powerful tools. The goal? To eventually replace most human studies with lab tests backed by science.

The Future: A Hybrid Approach

The future of bioequivalence isn’t in vivo OR in vitro. It’s in vivo AND in vitro-with modeling tying them together. For simple, well-understood drugs, in vitro testing will dominate. For complex, high-risk, or poorly absorbed drugs, in vivo will remain essential. The FDA’s 2023 White Paper on Modernizing Bioequivalence says it clearly: in vitro methods should be the primary tool for most generics, with in vivo studies reserved for high-risk cases. That means fewer people need to volunteer for studies. Faster approvals. Lower costs. More access to affordable medicines. But it also means regulators and manufacturers must invest in better lab methods, better models, and better validation. The $85,000-$120,000 flow-through dissolution apparatus isn’t just expensive-it’s necessary. Scientists need training in biopharmaceutics, not just chemistry. Regulatory teams need to understand modeling, not just paperwork.What This Means for You

As a patient, you don’t need to know the details. But you should know this: when you take a generic drug, it’s been proven to work like the brand. Whether that proof came from a blood test or a lab beaker, the standard is the same. And that standard is getting smarter. The shift toward in vitro testing isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about using better science. It’s about doing more with less. And it’s about getting safe, effective medicines to more people, faster.What’s the difference between in vivo and in vitro bioequivalence testing?

In vivo testing measures how a drug behaves in the human body, usually by taking blood samples to track drug levels over time. In vitro testing measures physical and chemical properties of the drug in a lab-like how quickly it dissolves or how particles are sized-without using people. In vivo tells you what happens in the body; in vitro tells you what the drug is capable of doing under controlled conditions.

Why is in vitro testing cheaper and faster than in vivo?

In vitro testing doesn’t require human volunteers, clinical sites, or long study periods. A dissolution test can be done in weeks for under $150,000. In vivo studies need 24+ healthy participants, ethics approvals, multiple blood draws over months, and specialized clinical units. That pushes costs to $500,000-$1 million and timelines to 3-6 months.

Can all generic drugs be approved using in vitro testing?

No. In vitro testing is only accepted for specific cases: highly soluble and permeable drugs (BCS Class I), complex delivery systems like inhalers or nasal sprays, or when a validated in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) exists. For drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes (like warfarin), food-dependent absorption, or nonlinear metabolism, in vivo testing is still required.

What is a biowaiver?

A biowaiver is when regulatory agencies like the FDA allow a generic drug to be approved without conducting a human bioequivalence study. This is typically granted when in vitro data (like dissolution profiles) are strong enough to predict that the drug will behave the same in the body. In 2021, 78% of BCS Class I generic applications received biowaivers.

Is in vitro testing more accurate than in vivo testing?

It’s more precise, but not always more accurate. In vitro methods have lower variability (CV under 5%) because they’re controlled. But they can’t replicate the full complexity of the human body-like gut motility, enzyme activity, or food effects. In vivo testing captures real-world behavior, even if it’s noisier. The best approach combines both: using in vitro to screen and in vivo to confirm when needed.

How does the FDA decide which method to require?

The FDA looks at the drug’s properties: solubility, permeability, therapeutic index, delivery method, and whether there’s an established in vitro-in vivo correlation. For simple oral tablets, in vitro may be enough. For inhalers, nasal sprays, or drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, in vivo is required. They also consider scientific evidence, past approvals, and emerging models like PBPK.

Are there any risks in relying on in vitro testing?

Yes. If the in vitro method doesn’t accurately reflect real human absorption, a generic might be approved that doesn’t work the same in patients. That’s why regulators require rigorous validation. A 2023 post-marketing study found that a topical antifungal approved via in vitro data had inconsistent patient outcomes, leading to a costly follow-up in vivo study. The risk is low when guidelines are followed-but it’s not zero.

Brian Furnell

December 20, 2025 AT 19:10Let’s be real-BCS Class I drugs are the low-hanging fruit for biowaivers, but the real win is when you can apply this to BCS Class III or IV. I’ve seen dissolution profiles that look perfect on paper, then crash in vivo because of bile salt micelle interactions that no lab fluid replicates. We need better GI simulators, not just pH buffers. The FDA’s 2023 PBPK guidance is a step forward, but validation frameworks are still fragmented across regions.

And don’t get me started on how some CROs cut corners with dissolution apparatus calibration. I’ve reviewed data where the paddle speed drifted 5 RPM over 8 hours-and somehow, it still passed. That’s not science; that’s wishful thinking.

Siobhan K.

December 21, 2025 AT 03:54So let me get this straight-you’re telling me we spend $1 million to test 24 people’s blood, but we can replace it with a beaker and a laser? Sounds like corporate cost-cutting dressed up as innovation. The fact that we need a $85,000 dissolution machine just to prove a pill dissolves right says more about our priorities than our science.

Stacey Smith

December 22, 2025 AT 19:51USA leads in this. Other countries still cling to outdated human trials. Time to catch up.

Ben Warren

December 23, 2025 AT 08:24It is imperative to underscore that the regulatory framework governing bioequivalence is not a mere procedural formality; it is, in fact, a rigorous, evidence-based paradigm grounded in pharmacokinetic principles, statistical rigor, and clinical relevance. The conflation of cost-efficiency with scientific validity represents a dangerous epistemological drift, wherein instrumental rationality supersedes epistemic integrity. The assertion that in vitro methods are inherently superior is not only empirically unsound but also ethically precarious, given the inherent variability of human physiology, which cannot be adequately modeled by artificial dissolution media.

Furthermore, the normalization of biowaivers for non-BCS Class I compounds constitutes a systemic erosion of the precautionary principle, potentially exposing vulnerable populations to subtherapeutic or toxic drug exposure. The FDA’s increasing reliance on PBPK modeling, while theoretically elegant, remains insufficiently validated across diverse ethnic and metabolic phenotypes. One must ask: are we optimizing for efficiency-or are we optimizing for risk?

The recent approval of a generic nasal spray based solely on cascade impactor data, while technically compliant, fails to account for inter-individual variations in nasal mucosal absorption, ciliary clearance, and mucus viscosity-all of which are dynamically modulated by environmental, pathological, and pharmacological factors. This is not progress. This is precarity masquerading as innovation.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 24, 2025 AT 07:42It’s fascinating how the industry frames this as a win for patients. But let’s not ignore the fact that behind every biowaiver is a team of scientists who spent months validating a dissolution method-often with no guarantee of approval. The real cost isn’t in human trials; it’s in the years of R&D that get buried under regulatory uncertainty. We need more transparency in validation criteria, not just faster approvals.

Sandy Crux

December 24, 2025 AT 15:39Oh, so now we’re trusting a beaker over a human body? How quaint. Next they’ll replace MRI scans with a ruler and a guess. The fact that regulators accept this as ‘science’ is a testament to how far we’ve fallen from empirical rigor. In vitro data is a proxy-a crude one at that. And proxies, by definition, are wrong. Sometimes dangerously so.

And don’t even get me started on ‘validated IVIVC.’ That’s just a fancy way of saying, ‘We got lucky once, so let’s pretend it always works.’

Hannah Taylor

December 26, 2025 AT 07:52theyre just hiding the truth. big pharma and the fda are in cahoots. they dont want you to know that generics sometimes dont work right. thats why they push in vitro-its easier to fake data in a lab than in a person. remember that antifungal that failed? they buried the reports. trust me, i’ve seen the emails.

Michael Ochieng

December 28, 2025 AT 00:16I’ve worked on generic inhalers in Nigeria and Canada-same tech, different outcomes. The lab data looked perfect, but patients in Lagos had worse symptom control than those in Toronto. Turns out, humidity and storage conditions affected the propellant. In vitro can’t capture that. We need global standards-not just FDA-approved methods.

Dan Adkins

December 29, 2025 AT 10:32It is a matter of profound concern that the regulatory apparatus, particularly within the United States, has increasingly prioritized expediency over evidentiary integrity. The reliance upon in vitro methodologies for bioequivalence determination-particularly in the absence of robust, prospectively validated IVIVC-is not merely an administrative convenience; it constitutes a systemic abdication of the duty to protect public health. The statistical parameters governing bioequivalence (80–125%) were established under conditions of physiological variability, which in vitro systems, by their very nature, cannot replicate. To assert that dissolution profiles alone are sufficient for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices is not only scientifically indefensible-it is ethically reckless. Furthermore, the promotion of PBPK modeling as a replacement for empirical human data reflects a dangerous technocratic hubris. Models are not observations; they are approximations, often calibrated on homogeneous populations, and therefore ill-equipped to predict outcomes in genetically diverse, comorbid, or polypharmacologically complex individuals. The erosion of in vivo requirements is not innovation-it is institutional negligence dressed in the language of progress.